RATTIN IS AT A ALL TIME HIGH, SOMETHINGS WE WILL NEVER FIND OUT ABOUT!

BUT MOST THINGS COME TO THE LIGHT!

SO IF YOU WAS THINKING YOU COULD SNITCH AND GET AWAY WITH IT...THINK AGAIN!

*THIS IS A REAL COURT APPEAL DOCUMENT*

(BEFORE YOU CALL SOMEONE A RAT YOU MUST HAVE PROOF!)

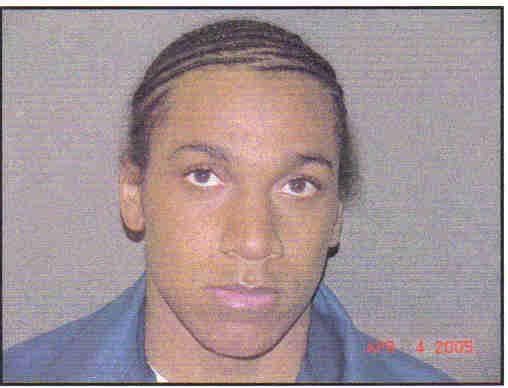

PEOPLE OF THE STATE OF MICHIGAN, Plaintiff-Appellee, UNPUBLISHED March 6, 2003 v No. 232862 Kent Circuit Court KENNETH CARTER, JR., a/k/a FRED JOHNSON, a/k/a/ WILLIE KADO, LC No. 00-008812-FCDefendant-Appellant. Before: Meter, P.J., and Neff and Donofrio, JJ.PER CURIAM.

Defendant appeals by right from his conviction by a jury of first-degree premeditated murder, MCL 750.316, assault with intent to commit murder, MCL 750.83, and possession of a firearm during the commission of a felony, MCL 750.227b. The trial court sentenced him to concurrent terms of life imprisonment without the possibility of parole for the first-degree murder conviction and twenty to forty years' imprisonment for the assault conviction, to be served consecutively to a two-year term for the felony-firearm conviction. We affirm. Defendant's convictions arose from a shooting incident that occurred during the earlymorning hours of November 1, 1999. Ruben Vance died from a single gunshot wound to his head. Jamar McDonald, the other victim, was not injured during the assault.

Defendant first argues that the prosecutor presented insufficient evidence to prove beyond a reasonable doubt that he was the person who shot several times at the Monte Carlo automobile, in which the two victims were seated. Defendant argues that there was evidence thatDamien Baker, the driver of the white Grand Am from which the shots were fired, could have committed the shootings. Defendant also argues that all of the witnesses who placed him at the shooting scene or identified him as the shooter were unbelievable because they either testified pursuant to plea agreements or testified contrary to earlier statements or testimony. In reviewing the sufficiency of the evidence, we "must view the evidence in a light mostfavorable to the prosecution and determine whether a rational trier of fact could find that the essential elements of the crime were proved beyond a reasonable doubt." People v Hoffman, 225 Mich App 103, 111; 570 NW2d 146 (1997), citing People v Wolfe, 440 Mich 508, 515; 489 NW2d 748 (1992), amended 441 Mich 1201 (1992). All conflicts with regard to the evidence must be resolved in favor of the prosecution. People v Terry, 224 Mich App 447, 452; 569

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Page 2

-2- NW2d 641 (1997). Further, this Court should not interfere with the jury's role of determiningthe weight of the evidence or the credibility of witnesses. Id.; Wolfe, supra at 514-515. The evidence presented, viewed in the light most favorable to the prosecution, was sufficient to establish defendant's identity as the shooter. DeYoka Freeman testified that duringthe early morning hours of November 1, 1999, he saw defendant in the passenger seat of a white Grand Am in the parking lot of the Amoco Station on Division and Hall Streets in Grand Rapids. Freeman testified that he observed the Grand Am exit the parking lot of the station and subsequently return, after which numerous gunshots erupted from the Grand Am. Kevin Buchanan, who was with Freeman, confirmed that defendant was in the passenger seat of the Grand Am at the time of the shooting. Additionally, Buchanan specifically identified defendant as the person who shot at the Monte Carlo from the passenger side of the Grand Am. Baker also identified defendant as the shooter.

McDonald, the driver of the Monte Carlo, conceded that the driver of the Grand Am could have been the shooter, but he testified that he believed that the passenger did the shooting and that he saw a gun hanging out of the passenger window. Sheila Williams testified that she saw defendant in the passenger seat of the white Grand Am shortlybefore the shooting. Moreover, Thomas Birge, Baker's father, testified that when Baker and defendant arrived at Birge's house in the early morning hours of November 1, 1999, defendant handed an empty gun to Birge, which Birge reloaded using forty-caliber ammunition later seizedby the police. The ammunition used by the shooter at the gas station was forty-caliber ammunition. Ira Miller testified that when he asked defendant about the shooting, defendant said he "popped the ni---r, it's done and over with, you know what I'm sayin', f--k it." A crime scene technician concluded that the evidence supported the prosecution's theory that the passenger of the Grand Am was the shooter, assuming that at the time of the shooting, the passenger side of the Grand Am was closer to the Monte Carlo than the driver's side of the Grand Am.

Evidence at trial supported that the passenger side of the Grand Am was closer to the Monte Carlo. The above evidence, if believed, was sufficient to support defendant's convictions. Although many of the witnesses testified in exchange for plea deals or otherwise had credibilityissues, it was the role of the jury to determine credibility. Wolfe, supra at 514-515; Terry, supra at 452. We will not interfere with the jury's role in that regard. We therefore reject defendant's argument that the evidence was insufficient to support his identity as the shooter. Next, defendant argues that the trial court abused its discretion when it admitted into evidence a photograph of defendant's brother. Defendant was carrying the photograph at the time of his arrest. It depicted his brother, Quentin Carter, dressed as a gangster and holding amachine gun. Defendant argues that the photograph was irrelevant and, even if minimallyrelevant, the probative value of the photograph was substantially outweighed by the danger of unfair prejudice. Defendant objected to the admission of the photograph only on the ground that it should be excluded under MRE 403. He never argued that the photograph was irrelevant. An objection on one ground is insufficient to preserve an appellate challenge on another ground. People v Canter, 197 Mich App 550, 563; 496 NW2d 336 (1992). We review the unpreserved allegation that the evidence was irrelevant for plain error. People v Carines, 460 Mich 750, 763-764; 597 NW2d 130 (1999).

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Page 3

-3- In a murder case, motive is generally relevant to show the intent necessary to provemurder. People v Herndon, 246 Mich App 371, 412-413; 633 NW2d 376 (2001). The intent to murder is also an essential element of the crime of assault with intent to commit murder. People v McRunels, 237 Mich App 168, 181; 603 NW2d 95 (1999). Circumstantial evidence and reasonable inferences drawn from that evidence may constitute satisfactory proof of thatelement. Id. In this case, the prosecutor offered evidence that defendant's motive for the shooting was revenge for the killing of his brother. There was evidence that the Lafayette gangand the Wealthy Street gang did not like each other. Defendant grew up on Lafayette and knew his brother was killed by Terrance Williams, a member of the Wealthy Street gang. Defendant was badly affected by his brother's death. There was also evidence that Vance lived on WealthyStreet and that the case against Williams for Quentin Carter's murder was dismissed. Theprosecutor used the photograph to support the offered motive, that defendant shot at the victims as an act of revenge for the killing of his brother, whom defendant cherished and whose picturehe carried with him. The evidence was relevant because it tended to prove motive. We thus can discern no plain error in the admission of the photograph as relevant evidence.

In addition, the trial court did not abuse its discretion in admitting the evidence over defendant's objection based on MRE 403. MRE 403 provides that evidence may be excluded "if its probative value is outweighed by the danger of unfair prejudice, confusion of the issues, or misleading the jury, or by considerations of undue delay, waste of time, or needless presentation of cumulative evidence." Moreover, [t]he decision whether to admit evidence is within the discretion of thetrial court and will not be disturbed on appeal absent a clear abuse of discretion. An abuse of discretion is found only if an unprejudiced person, considering the facts on which the trial court acted, would say that there was no excuse for the ruling made. A decision on a close evidentiary question ordinarily cannot be an abuse of discretion. [People v Aldrich, 246 Mich App 101, 113; 631 NW2d 67 (2001) (citations omitted).]The photograph at issue was described by the prosecutor at trial as a "fantasy" photograph. It depicted defendant's brother in a staged, gangster-like pose. The photograph was clearly not a picture of defendant's brother engaged in gang or criminal activity. Further, thephotograph did not portray defendant or reflect on his character or activities. Moreover, defendant does not argue that the photograph confused the issues, misled the jury, or caused undue delay. Under the circumstances, we cannot find an abuse of discretion in the trial court's ruling on this evidentiary question. Moreover, even if the trial court had erred in admitting thephotograph, we would nonetheless find no basis for reversal under the harmless error standard from People v Lukity, 460 Mich 484, 495-496; 596 NW2d 607 (1999). Next, defendant argues that the trial court erred by failing to give the standard cautionaryinstruction on accomplice testimony. Defendant neither requested the instruction nor objected to

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Page 4

-4- its omission. Thus, the issue is not preserved. People v Lee, 243 Mich App 163, 183; 622 NW2d 71 (2000).1In People v McCoy, 392 Mich 231, 240; 220 NW2d 456 (1974), the Court ruled that error requiring reversal may be found if a trial court fails to give a cautionary instruction on accomplice testimony, even in the absence of a request for such an instruction, if the case is closely drawn. A case is closely drawn if a determination of the defendant's guilt essentiallycomes down to a credibility contest between the defendant and his accomplice. People v Perry,218 Mich App 520, 529; 554 NW2d 362 (1996). In People v Reed, 453 Mich 685, 692; 556 NW2d 858 (1996), the Court clarified that the McCoy rule "does not require automatic reversal when a case is 'closely drawn' and a judge fails to give such an instruction sua sponte." The Reed Court stated: Rather, McCoy states that such a failure to instruct may be error requiringreversal. This Court has never established standards for evaluating when the failure to instruct sua sponte requires reversal. In People v Atkins, 397 Mich 163; 243 NW2d 292 (1976), for example, we declined to extend McCoy to a case involving an addict-informer. One of the reasons was that defense counsel had thoroughly explored the addict-informer's motivation to lie on cross-examination. Id. at 168, 171-172. Clearly, it would make little sense to require a judge to caution a jury sua sponte on a witness' motivation to lie when defense counsel has thoroughly explored the witness' motivations. Rather, McCoy stands for the proposition that a judge should give a cautionary instruction on accomplice testimony sua sponte when potential problems with an accomplice's credibilityhave not been plainly presented to the jury.

[Reed, supra at 692-693 (emphasis in original).] In this case, the problems with Baker's testimony were thoroughly explored by defense counsel and were presented to the jury. Defense counsel extensively cross-examined both Baker and Detective Mark Groen about Baker's motivations for testifying and about inconsistencies between Baker's trial testimony and his original statement to the police. In addition, this is not a case where defendant's guilt was closely drawn. It was not a credibility contest between defendant and Baker because other witnesses testified that defendant was in the passenger seat of the Grand Am, and evidence other than Baker's testimony identified the passenger as the shooter. Moreover, Buchanan expressly identified defendant as the shooter. Therefore, the trial court's failure to sua sponte give the standard cautionary instruction on accomplice testimony did not amount to plain error. Moreover, even if a plain error were apparent, defendant cannot 1We note that defendant raised the instructional issue in his post-trial motion for a new trial. Weconclude, however, that this was insufficient to preserve the issue. In Carines, supra at 761-762, the Court noted that litigants are encouraged to seek a fair and accurate trial the first time around and that trial is the best time to address a defendant's constitutional and nonconstitutional concerns. The Carines Court treated the defendant's allegation of instructional error as unpreserved because the defendant failed to object to the instructions at trial. Id. at 761. Here, because defendant did not raise the instant issue at trial, it is unpreserved

No comments:

Post a Comment